Ever built a house? Then you know how critical it is to lay the foundation, and to lay it right.

Research is arguably the second most critical step in the development of a veterinary medical illustration. Once the plans are made, research is the foundation of the final artwork that will provide stability to the overall structure.

Research, for some, can also be yawn inducing (see the rough sketch on the right)! In the interest of saving time and money, it is often overlooked. But paying careful attention to this step, we actually save time and cost for clients.

Case in point – a recent mistake regarding a backwards human brain portrayed in an ad campaign for the University of Southern California Neuroimaging and Informatics Institute, of all ironies. This embarrassing mistake could have been prevented by hiring a professional medical illustrator and by doing proper research on human neuroanatomy.

I’m letting you in on a little secret here: artists like to reference what other artists did before them. I’m not talking about copying, which is plagiarism and copyright infringement. If a user likes what an artist created, then they should contact the rights holder and purchase the appropriate license or permissions to use that artwork.

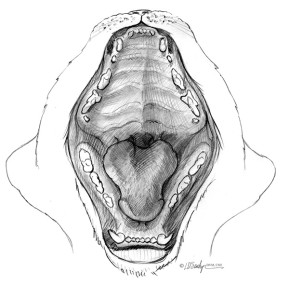

There is actually not much harm in this type of referencing on the surface. We want to see if a subject has been portrayed, how, and more importantly, we don’t want to copy exactly what another did. We can also use a variety of drawn references to help check ourselves. If 9/10 artists labeled three right mandibular premolar teeth in the cat, we figure we should do it, too. Right?

But here’s where it gets dicey. There’s a lot of beautiful detailed artwork out there. And there’s a lot of beautiful inaccurate artwork out there. Many times, the inaccuracies are not easily noticed, and sometimes, they’re glaring. But hey, how bad can it be?

Along with being an embarrassment to a client, it can be a concern. Because the artwork is used to communicate and inform, we could be delivering the wrong message. Is a surgeon reading a textbook illustration going to cut the wrong artery? I hope that either the artist or the editor caught that one.

Some error is inevitable. I hope that a mistake in a drawing would rarely cost life or limb. But it is why I pay special attention to reasonably collecting all the data I can about a project. Getting to know the subject matter. Talking with experts. Reading peer-reviewed scientific literature. Viewing a procedure. Drawing from life or cadaver specimens. And so on.

Any artist can do these things. But a medical artist already has the foundation of medical and scientific language united with art and design training, so they acclimate easily. Our firm specializes in veterinary content expertise, so we’re going to have more familiarity with veterinary subject matter. Real doctors treat (and artists draw) more than one species! Kidding – we love human animals, illustrators, and physicians, too.

So back to the cat. Nine out of 10 images done by the other artists showed the cat has three right mandibular premolar teeth. But guess what? Cats have two mandibular premolar teeth on the right side (and the left side too – no lopsided felines here). And adult cats have one molar tooth on the right and left mandibular sides. It’s also valuable to know that cats are not small dogs. And we knew this because of our anatomical training, clinical experience, and research. And there is great value to bringing this knowledge to your project.

In the next article, we’ll begin working on our project with Rough Sketches: The Basic Framework.